We failed to quantify quality Airmen

A couple weeks ago I wrote about a FOIA request I submitted in July 2019. The intent of the request was to bring clarity to the career fields impacted by the ongoing suicide epidemic in the Air Force. If you remember, the response was flaccid.

I went on to show how the current AF/A1 Lt. Gen. Brian Kelly was dishonest when he gave an interview in 2015 suggesting that critical career fields were somehow shielded from the Force Reduction measures, colloquially called "The Air Force Hunger Games."

I went on to show how the current AF/A1 Lt. Gen. Brian Kelly was dishonest when he gave an interview in 2015 suggesting that critical career fields were somehow shielded from the Force Reduction measures, colloquially called "The Air Force Hunger Games."But to simply say certain career fields were cut is insufficient to explain how the cuts were determined and, moreover, which discriminators were used. And for that, we need to go back a ways...

In early 2011 the Air Force had transferred many SSgts and TSgts from fighter maintenance to heavy aircraft in an effort to shore up their issues in the heavy world. In effect, robbing Peter to pay Paul. This left us with a slightly lopsided organization: thick in the SNCO ranks, thin in the middle tier, and an overabundance of young 3 and 5 skill levels.

In 2012 I was a Flightline Expediter in the 308th AMU at Luke Air Force Base. At the time, the 308th was on the cusp of a death spiral, although we didn't know it. Between the reduction of experienced NCO's, an influx of brand new Airmen and an avionics upgrade we lacked the resources to meet the mission. And it was only going to get worse.

However, also in 2012 I met A1C Boushon Arnold.

Arnold had been in the unit maybe a week when I happened to be turning-over from the day shift expediter. As I was getting updates on aircraft re-configs I noticed something strange: Arnold was leading a wing tank installation.

You see, there is a certain type of learning curve when it comes to aircraft maintenance. The fact Arnold was leading the installation after being on the flightline for only a week was impressive. At the end of the shift I approached him to introduce myself. He immediately asked if I could help him "get on swing shift." I approached the section chief that day and Arnold was transferred to swings the following week.

If you're not familiar with aircraft maintenance you may not realize that swing shift typically does the heavy lifting for the maintenance effort. Day shift is more of a triage, fixing the jets that are on the flying schedule and doing what you can for the remaining broken aircraft. As such, swing shift can be a bit of a "feast or famine" type of environment. Some nights you may only work 3 hours, other nights it could be 15 or more.

Of course, in the 308th in 2012, there weren't really any 3 hour nights; or 8 hours nights. Eleven to 15 was the norm. One night in particular Arnold had a mandatory appointment the next day and I met up with him around his 8 hour mark to release him [12 hours before the appointment].

He protested.

He thought there was too much work, and that he shouldn't leave. I wasn't swayed and I told him to check with the section chief and go home. As the night went on I drove from jet to jet getting status updates.

Five hours later I was cleaning out my truck for turn-in and I saw Arnold walking over from the ECP. He had never left. He had stayed because he knew the rest of us were worn out and needed the help. He also hid from me every time I drove by because he knew if I caught him I would make him go home. I was livid.

In his response he pointed out that I regularly worked 15 hours or more and sometimes I would have an appointment in the morning; and yet, I didn't leave work early. I explained that as a TSgt I had a different set of rules and responsibilities.

He replied simply "That doesn't make sense."

As the death spiral continued and our workdays grew longer I leaned heavily on Arnold. His work ethic was undying, and his attitude was always positive. At one point I told him he was lucky. He had joined the Air Force during a time of severe resource restriction. Which to me, meant Arnold was learning how to be "poor" in the Air Force, and was a valuable first lesson.

Beyond his work duties he was completing his CDCs[Career Development Course] on track and had volunteered to be in Honor Guard. And yet, he still maintained his same work ethic and positive attitude. Moreover, his technical and leadership abilities were growing exponentially.

Beyond his work duties he was completing his CDCs[Career Development Course] on track and had volunteered to be in Honor Guard. And yet, he still maintained his same work ethic and positive attitude. Moreover, his technical and leadership abilities were growing exponentially.In 2013 I transitioned to be his section chief as I had a line-number for MSgt. In the same year, Arnold's dedication to the mission finally caught up with him. He failed his first PT test. He completed 41 sit-ups, falling one short of the mandatory minimum of 42. Even though his overall score was still passing.

He signed onto the Commander's PT program. You could tell it affected him. Not just the shame of failure, but knowing that his time in the PT program would count towards his work hours, which meant he was contributing less than his peers. His failure would hurt the rest of the team. That's a tough pill to swallow.

He attacked the Commander's PT program with the same work ethic he had on the flightline. He got his mile-and-a-half down to the low 10's and his push ups were maxed. Unfortunately, he was still struggling with sit-ups.

So I asked him to show me what he was doing. We headed to the support section[for the rubber floor] to have him demonstrate. After the first few sit-ups I knew what was wrong. He was doing them too well. The Air Force fitness regulation only required the elbows to touch the thigh on the 'up' and the shoulder blades to touch the ground on the 'down.' Arnold was doing full sit-ups.

So basically, I began coaching him on how to do his sit-ups worse. In essence, to lower his personal standard to meet the Air Force's standard. How utterly backwards.

Unfortunately, he failed again. He received a Letter of Reprimand and Unfavorable Information File from the Commander.

To make matters worse, this failure happened at the end of 2013 when the Air Force was ramping up their FY14 Force Reduction measures. As such, Arnold was vulnerable to involuntary separation.

But, Arnold was lucky. Everyone knew he was smart, hard working and a natural leader. Every single person in his chain ranked him at the top of the list for retention.

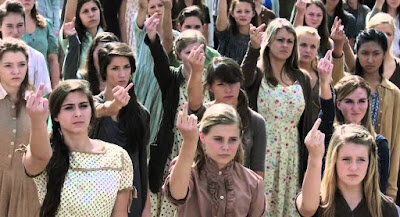

In the spring of 2014 AFPC coordinated the notification for all the affected Airmen to let them know if they were retained or separated. At the time I was the Acting First Sergeant so I had to coordinate the notifications.

To my utter and complete dismay I saw that A1C Boushon Arnold was not selected for retention.

Of all of the mistakes I had witnessed in my career [which were numerous], this one was the absolute worst. How? How could AFPC ignore everything we were saying about the quality of this Airman that they went against our recommendations and elected to separate him.

I did what I could to soften the blow and support Arnold as he transitioned out. I solicited people in our chain to write him letters of recommendation to help him in his job hunt.

In the summer of 2014 I PCS'd to Holloman AFB. After a few months I received a phone call. The woman on the phone said that a Boushon Arnold had put me down as a reference for a job. I spent the next 20 minutes explaining why he was one of the best workers I had ever had, and it was a huge mistake that we let him go. That I would gladly work with or for Boushon in a heartbeat. She said it was the best recommendation she had ever received.

Before she hung up I asked what job he was applying for. She responded that he was applying to be a janitor at a local school.

Even now I'm both angry and proud. Angry that the Air Force just absolutely squandered a promising Airmen. Angry that his talents were being wasted doing such a mundane task. But, I was also proud that he was doing what needed to be done to support himself and his family. That he wouldn't let his pride get in the way of building the life he deserved.

I reached out to Boushon Arnold as I was writing this. He told me that he is now working for a tech company making good money and is in a healthy work environment. Maybe in the end, the Air Force didn't deserve Arnold.

But it got me thinking.

How many Arnolds were cut in 2014? I certainly know of the one, but how many others were there? How did AFPC decide who to cut?

It clearly didn't consider the Commander's input. Which would be the only source of information on member's work ethic, teamwork, leadership, followership, technical expertise, morals/ethics, and attitude.

So what discriminators selected who was vulnerable for Force Reduction in the first place? They called them QFIs or Quality Force Indicators. Article 15s, EPR markdowns, UIFs, Control Rosters, PT failures, etc. None of these indicators in-and-of themselves give any evidence of contribution to the mission, or a lack thereof. And yet, this is how we decided who the Air Force was going to get rid of.

We picked the things that didn't matter, ignored testimonials from their direct supervisor and commander, and separated Airmen based on these metrics.

So the odds that we lost only one Boushon Arnold of the approximately 17,000 people cut is probably low. Because we were trying to quantify intangible qualities and ignoring the front-line supervisors telling us not to cut these people.

In writing this story I spoke with someone who was a squadron commander during the FY14 Reduction at another base. When asked whether AFPC used commander recommendations in deciding who to retain, he stated "I didn't feel like they considered my input when I tried to save an [airman]."

So how many Arnolds did we lose?

You're welcome to join us on our Facebook page. If you know of other Airmen like Arnold let us know in the comments!