The Frayed Ends of Accountability

Recently The Intercept published an article titled “The Business of Killing – Newly Released Data Reveals Air Force Suicide Crisis After Years of Concealment.”

This is the story of that concealment.

Pulling the First Thread

It began with my retirement from the Active Duty(AD) United States Air Force(USAF) in 2018. For the sake of brevity I was an F-16 Crew Chief for 20 years and saw first hand the dysfunction and social toxicity in the aircraft maintenance community. I was subjected to it, and later in my career I joined in it. After retiring I wanted to better understand what influenced me to behave in such a way, that in retrospect, was toxic.

After my retirement I started the 20 Years Done Blog to essentially process my career and pass along insights and information to a small audience. In October 2018, the Secretary of Defense (SECDEF) Jim Mattis had directed five fighter airframes to reach an 80 percent readiness rate, often referred to as “MC Rate” within 12 months. This mandate was colloquially referred to as MC-80. I was alarmed and wrote a blog post titled The Crisis in Aircraft Maintenance as a warning that this mandate would decimate the USAF aircraft maintainers due to the career fields being overworked, under-resourced, and generally culturally toxic.

In January 2019 an AD airman stationed at Holloman Air Force Base (AFB) that had worked for me in 2016 died by suicide. Within the same week, another aircraft maintainer at Holloman also died bysuicide. Within two weeks, a third maintainer at Luke AFB (Holloman’s F-16 parent duty station) attempted suicide. I believed there was an unfolding mental health crisis in USAF aircraft maintenance due to more than a decade of over-work, under-resource, and the resulting abuse.

In July 2019 I submitted a Freedom of Information Act(FOIA) request to Headquarters Air Force (HAF) A1 department (A1 is the personnel directorate) and the HAF/SG department (Surgeon General directorate). The request was for a breakdown of AD USAF suicides by Air Force Specialty Code (AFSC). Each service branch has individualized occupational codes for each of their career fields. They are unique to each service.

In August of 2019 the Air Force publicly announced they were on pace to have more AD suicides that year than in its history.

In September of 2019 I started my first year of law school. January 2020, the Air Force provided a response to my FOIA request.

“No responsive records.”

Their position was that suicide data by AFSC didn’t exist.

I called Air Force Public Affairs for comment. I told the officer I had received a “no records” reply. I asked the question directly: was the Air Force lying or incompetent?

She put me on hold. When she came back, she spoke off the record (later confirmed on the record by Chief Master Sergeant Perry, the Air Force First Sergeant Functional Manager). She said the data existed but the Air Force wasn’t the release authority. Instead of referring the request to the Defense Health Agency(DHA), they closed it as “no records.”

The Air Force re-submitted my FOIA on my behalf and I went back into a holding pattern waiting on a response. It would take until December 2020 for DHA to respond.

The data existed. I got the sense the Air Force, or the Department of Defense(DoD), just didn’t want to release it.

Pulling More Threads

I hypothesized that certain military career fields experienced higher rates of suicide compared to others. Getting those numbers was the first step. I knew once I got the data, there would be more questions. So I submitted more FOIA requests to be prepared to address those questions.

In February 2020 I submitted a FOIA request to the Air Force Personnel Center (AFPC) requesting a list of how many of each AFSC were separated during the 2014 sequestration personnel reductions. The 2014 sequestration personnel reductions represented one of the steepest cuts in personnel culminating in the lowest end-strength population of active-duty Airmen in this history of the USAF.

This was the next step as I was seeking to show three things:

1. The AD USAF abruptly separated a considerable amount of aircraft maintainers.

2. Prior to these personnel cuts the USAF fighter aircraft fleet was not healthy

3. There was not a reduction in aircraft maintenance workload after the personnel cuts.

The AFPC FOIA request addressed #1 above.

In March 2020 AFPC responded.

“Unable to fulfill request”

AFPC claimed they had no such break-out of which career fields were separated under sequestration and by law they were not required to create one for a FOIA request.

Undeterred, I submitted a FOIA request to the Air Force Manpower Analysis Agency (AFMAA) requesting end-strength numbers, how many raw numbers of each AFSC per year, from 2010 to 2019.

Concurrent to the manpower FOIA requests, I submitted FOIA requests to HAF/A4 (A4 is the aircraft maintenance directorate) requesting fleet health metrics for fighter aircraft from 2010-2014. Specifically, I requested data on F-22s, A-10s, F-15s and F-16s. For clarity, the fighter aircraft are broadly separated into two camps, 5th generation and 4th generation. F-22s and F-35s are 5th generation, whereas A-10s, F-15s and F-16s are 4th generation, also referred to as “legacy fighter” aircraft.

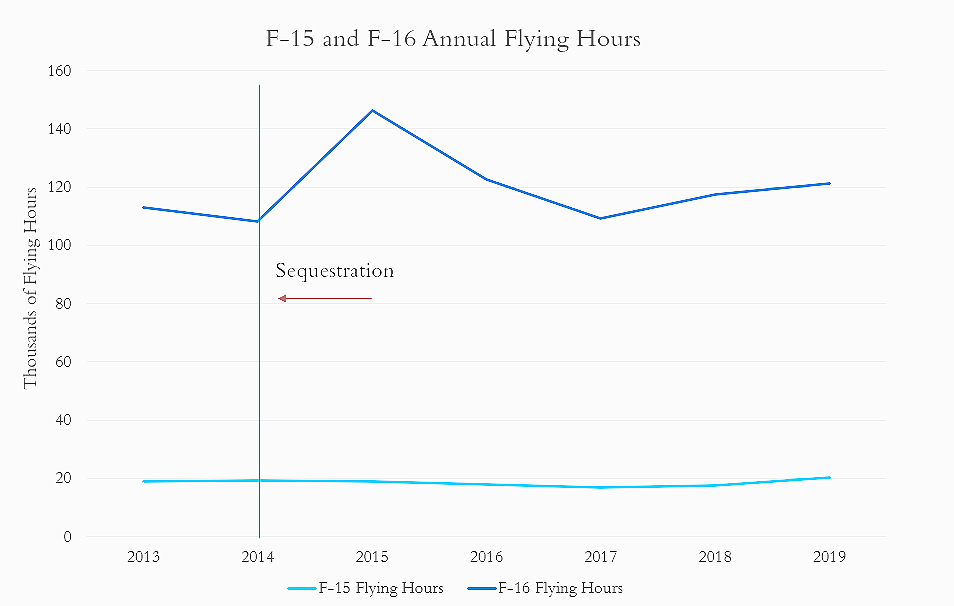

Additionally, I submitted a FOIA request to HAF/A3 (flight operations directorate) for the annual flying-hour totals for the selected airframes from 2013-2018. Flying hours are the most consistent measure of operational tempo across aircraft types. The goal was to show what the operational tempo was prior to sequestration (2013) and the years after (2014-2018).

Where the Threads Converge

The Fleet Health Thread

The first dataset I received came from HAF/A4 (I know we’re getting heavy on acronyms so I’ll toss a bone here. HAF/A4=logistics and maintenance directorate). It contained mission capable(MC) rates for fighter aircraft from 2010 to 2014. Essentially, the “readiness” requirement that SECDEF Mattis was focused on later in 2018.

The data showed that even when the Air Force had more maintainers and greater technical experience, the fighter fleet still fell well short of the 80 percent MC rate later demanded by Secretary of Defense James Mattis in 2018. The F-16 fleet peaked around 75 percent before trending downward, while the F-15 fleet rarely exceeded 70 percent.

The historical record made clear that the MC-80 directive was unsupported by past performance. Even under higher manning and stronger experience levels, the Air Force had never approached that threshold.

These findings confirmed what I had already seen before sequestration: the fleet was operating under strain, and leadership expectations were disconnected from the actual condition of both the aircraft and the people maintaining them.

The Operational Tempo Thread

The day after I received the mission capable rate data from HAF/A4, a second response arrived from HAF/A3 (flight operations directorate). This dataset contained annual flying hours for the F-16 and F-15 fleets(among other airframes) from 2013 through 2019.

The trend was unmistakable. Even after the 2014 sequestration cuts, the number of flying hours held steady and, in some years, increased. Despite having fewer maintainers, the Air Force maintained the same operational tempo.

The data made the imbalance clear. The service had reduced its manpower but continued demanding the same level of output. The remaining maintainers carried the full weight of that decision, and the strain was evident in both readiness and morale.

The Manpower Thread

Between 2012 and 2019, the manpower data revealed a consistent decline across multiple aircraft maintenance specialties. The Air Force had consolidated and later separated maintenance career fields between 2010 and 2012, creating inconsistencies in the earlier data. To maintain a uniform comparison, the analysis focused on the post-2012 period, when AFSC classifications stabilized.

Here is a capture of the raw data organized on an excel spreadsheet.

And here is the pertinent career field breakdown of manpower for three career fields.

The results showed that several maintenance AFSCs experienced significant reductions in personnel following the 2014 sequestration.

This reduction in manpower aligned with the broader findings from the fleet health and operational tempo data. The Air Force maintained consistent flight activity with fewer maintainers, supporting a fighter fleet that had been struggling for years to meet readiness requirements.

With these three datasets, the pattern was undeniable. The Air Force had built a system that demanded more than its people could sustain, and the data only hinted at the toll that would follow.

An Unexpected Thread

In December 2020 the Department of Defense/Defense Health Agency (DOD/DHA or DHA) had denied my request for suicides broken down by AFSC citing privacy concerns. I submitted an administrative appeal in March 2021 (which as of this writing in October 2025 still has not been adjudicated).

In November 2021, I recalled something significant. Back in 2016, the Air Force had introduced a computer-based training course titled Overwhelmed: Aircraft Maintainer Suicide Awareness Training.

The Air Force doesn’t develop suicide prevention training tailored to a specific career field without data demonstrating a clear need. If I could not obtain suicide rates by AFSC from the DOD/DHA, I reasoned I could locate the evidence that led to the creation of this course.

In November 2021, I submitted a FOIA request to Air Education and Training Command (AETC) Course Development, asking for all documents, messages, and studies used to justify the course’s creation.

In July 2022 I received a response to my FOIA request. The documents contained raw suicide counts by AFSC. For the first time, I could see the occupational breakdown they had claimed did not exist. More importantly, I could now pair those numbers with the end-strength data. Together, these datasets allowed me to calculate a per capita suicide rate for aircraft maintainers; something I had been trying to access for three years.

The course materials themselves were just as telling. They confirmed that by 2016, the Air Force was already aware of the scope and severity of suicide within the aircraft maintenance community. The training was not a proactive measure; it was a response to an ongoing crisis.

Slides from an April 1, 2016 presentation to Air Force Headquarters described a workforce under extreme pressure. Across nearly every Major Command (MAJCOM) and unit type surveyed, maintainers reported high levels of job stress, often citing it as a key reason for wanting to leave the service. Among flightline maintainers, 35 percent were already considering separating at the end of their commitment. Even more striking, those planning to leave weren’t looking for different roles within maintenance; they wanted out of the field entirely.

Among AFSCs 2A3, 2A5, and 2A7, between 74 and 77 percent of respondents said they would leave their specialty if given the chance.

However, the data painted a much more dire picture.

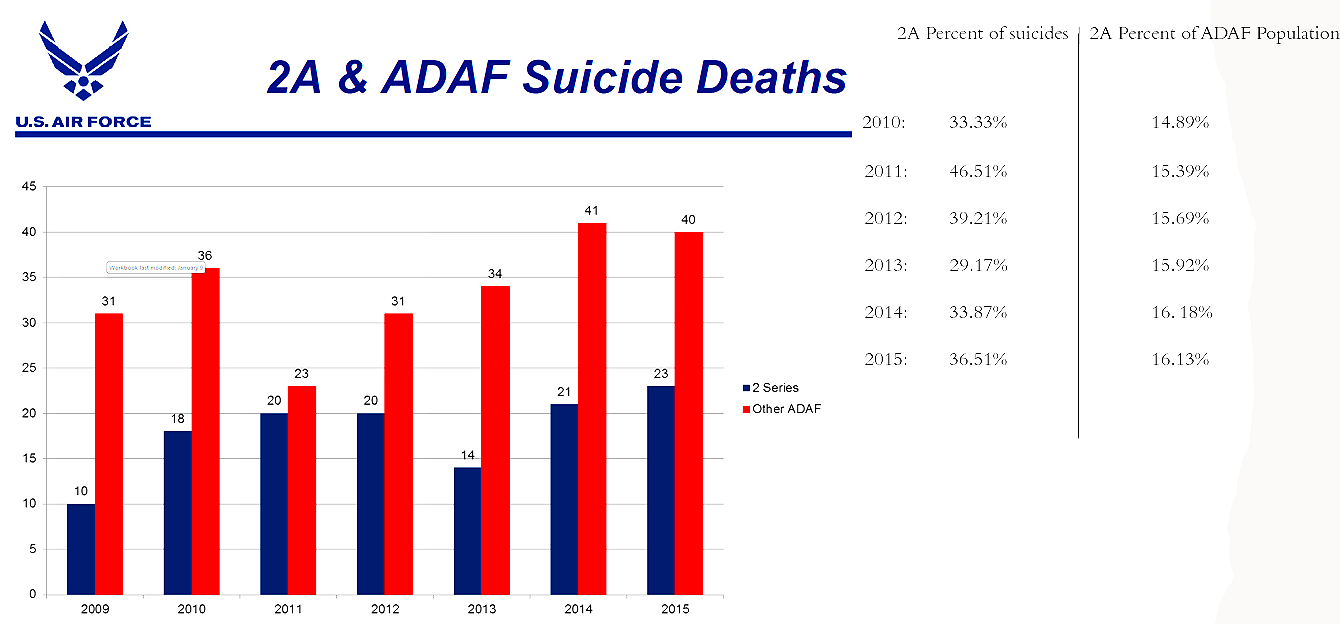

The dataset contained raw suicide counts by occupational field from 2009 through 2015. At the bottom of the table was a key figure: in 2009, the combined population of the listed career fields was 108,605. By 2015, that number had dropped to 89,201; reduction of nearly 18 percent. During that same period, suicides increased.

A closer look revealed another problem. The Air Force had aggregated a wide range of career fields into the same dataset, masking important differences in risk. Several AFSCs, such as 2E (ground communications), 2F (fuel systems), and 2S (logistics), showed little or no suicide activity, while aircraft maintenance-specific codes like 2A3 (fighter maintenance), 2A5 (cargo/bomber maintenance), 2A6(aircraft engine maintenance), and 2A7(aircraft structures maintenance) showed consistently higher numbers. Combining all of these fields together diluted the visibility of risk in the high-stress maintenance specialties. Even the per-100,000 suicide rate listed at the bottom of the table understated the problem because it included large populations of career fields with virtually no suicides.

Having already obtained end-strength data from 2010 through 2015, I was able to refine the analysis. By isolating the aircraft maintenance career fields and calculating their respective suicide rates per 100,000 personnel, a clear disparity emerged.

Between 2010 and 2015, aircraft maintenance AFSCs (2A) consistently accounted for a disproportionately high share of suicides relative to their size within the active-duty Air Force. Throughout this six-year period, maintainers made up only about 15 to 16 percent of the total active-duty population, yet they represented between 29 and 47 percent of all suicides each year.

In 2011, for example, 2A Airmen comprised just over 15 percent of the force but accounted for nearly 47 percent of suicides—more than triple their proportional representation. Even in the lowest year, 2013, maintainers still represented nearly one-third of all Air Force suicides while comprising less than one-sixth of its personnel.

These data points covered the years just before and during sequestration. The sharp rise in Air Force suicides that followed in 2019 was not fully captured here, but the foundation for that spike was already visible.

The trends in these early years showed where the system was beginning to fail; and where the warning signs were already flashing.

The Legislative Thread

Weaving the Law

In January 2022, I participated in Senator Angus King’s Library of Congress Veterans History Project, an initiative to record the experiences of Maine veterans (pardon my hair, it was COVID-ish). I didn’t know whether the conversation would remain a historical record or become an opening for meaningful change. By that point, I had already gathered extensive data through my FOIA requests; showing how fleet readiness declined, manpower dropped, and operational demands stayed high even as the force shrank.

When Senator King asked about fleet health, I was prepared to provide more than anecdote. I explained how years of strain had eroded maintenance capacity, how sequestration had accelerated the loss of skilled personnel, and how those pressures had created conditions that were breaking maintainers.

After the cameras stopped recording, I raised the issue that had driven much of my work: suicides among aircraft maintainers. I told him about the roadblocks I had faced trying to obtain suicide data by AFSC. He asked directly if I wanted him to get the data himself. I responded that he served on the Senate Armed Services Committee (SASC), and that the goal was not for me to have the data, it was for Congress to exercise their congressional oversight authority.

In February 2022, I joined a Zoom meeting with Jeff Bennett, Senator King’s National Security Advisor and retired Navy Captain, and another member of his staff to discuss how to obtain suicide data broken down by military occupation. We reviewed several possible approaches. Initially, it was suggested an independent report would be commissioned through the Government Accountability Office to ensure objectivity and limit the possibility of manipulation by the DoD. After further discussion, Jeff proposed that we allow DoD to conduct the study first, saying it would be useful to “see how they do.” Jeff then recommended drafting legislation that would require the department to produce a comprehensive report examining suicides by service-specific occupational code across all branches and components, covering the entire period of the Global War on Terror from 2001 to the present. I supported the approach immediately. While my focus had been on the Air Force, expanding the scope made sense. Each branch carries distinct operational demands, cultural pressures, and stressors that influence suicide risk. A study of that scale had the potential to expose both service-specific and systemic drivers of the crisis.

In June 2022, Senator King called to share the draft language being prepared for the Senate version of the Fiscal Year 2023 National Defense Authorization Act(FY23 NDAA). The provision he read directed the DoD to conduct a study of suicides disaggregated by service-specific military occupational code, year, and component (active duty, reserve, national guard) covering the entire Global War on Terror(9/11/2001) period through the present.

In December 2022, following weeks of debate in Congress over a potential government shutdown, the FY23 NDAA was signed into law by President Biden. Embedded within the legislation was Section 599, which required the DoD to provide suicide data disaggregated by service-specific military occupational code, year, and component. With its passage, DoD was placed under a clear legal mandate to produce a comprehensive occupational Suicide Report covering the post–September 11, 2001 period, with a deadline of December 31, 2023.

Here is a link to the law itself, Section 599 begins on page 221 of the pdf: 2023 National Defense Authorization Act

Between August and October 2023, I continued coordinating with Senator King’s office, primarily through his staffer, Teague Morris, who had first introduced me to the senator during the Library of Congress project. In October, Senator King sent two personal acknowledgments. The first was a full-size print of Section 599 of the Fiscal Year 2023 NDAA, signed by President Joe Biden, Speaker Nancy Pelosi, and Senate President Pro Tempore Patrick Leahy. At the bottom, Senator King had written a note: “To Chris – with thanks for the idea! – Angus.”

He also sent a personal letter expressing gratitude for my role in advancing the study of suicide rates by occupational code. In the letter, he credited my advocacy as the catalyst for the inclusion of the provision in the FY23 NDAA and assured me that the Department of Defense was on track to meet the report’s December 2023 deadline. He described my work as “character-driven leadership” and reaffirmed his commitment to continue addressing the mental health needs of servicemembers, veterans, and their families.

The Law Hits a Snag

On January 2, 2024, the first business day after the DoD missed its legal deadline to deliver the Report, I contacted Senator King’s office to ask about the delay. My inquiry was directed to Jeff Bennett.

During the call with Bennett, he appeared unconcerned about the delay and assured me that progress was being made. He stated, “I’m expecting to get the report,” and described the matter as “straightforward.” He emphasized that Senator King had repeatedly raised the issue with senior defense officials, saying, “It’s not just a one and done, our work isn’t complete at the bill.” Bennett insisted that the senator’s office was “applying constant pressure” to ensure the Report’s completion.

I also reached out to Representative Jared Golden’s office, given his position on the House Armed Services Committee, to determine whether he had any insight into the Report’s status. I never heard back from Congressman Golden’s office.

Unbeknownst to me, on January 12, 2024 the Acting Undersecretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness Ashish Vazirani sent a letter to the House and Armed Services Committee’s informing them that the “it had gathered the numbers for the by-occupation suicide report . . . [but] the data ‘requires more intricate statistical approaches to make appropriate and reliable comparisons.’ Vazirani estimated his office will submit the report June 28 — nearly six months late.” This was reported (and quoted here) by the Army Times on March 12, 2024.

The following paragraphs exist when I didn’t know there was a letter from DoD to Congress explaining the report was late. Please consider that information when evaluating Jeff Bennett’s communications.

On January 17, 2024, Jeff Bennett followed up by email regarding the overdue Report. He wrote, “I heard back from DoD, and the report is undergoing final review. I expect it shortly. The final review step applies to all reports, but it means that the substantive work and coordination is complete. We have a nomination hearing coming up and can raise this issue, too.”

I replied asking when the hearing would occur and whether the Report’s delay would be addressed. Bennett responded, “The hearing is next week but we will likely bring it up in a one-on-one call along with other matters where DoD needs to get us a response. We have a service under secretary appearing before the committee. I have done this in the past and achieved success.”

Despite these assurances, the issue was never raised during the hearing. The Report remained overdue, and Bennett’s repeated promises of oversight again failed to produce action.

In mid-February 2024, Senator King joined a Zoom meeting hosted by a local veteran organization. During the Q&A session, I raised my hand and asked whether he was aware that the DoD Suicide Report mandated by Section 599 of the FY23 NDAA had already missed its deadline, and whether he would apply pressure to ensure its release. He assured me he would. It was the first time I confronted him directly rather than working through his staff, ensuring that his awareness of the missed deadline was irrefutable.

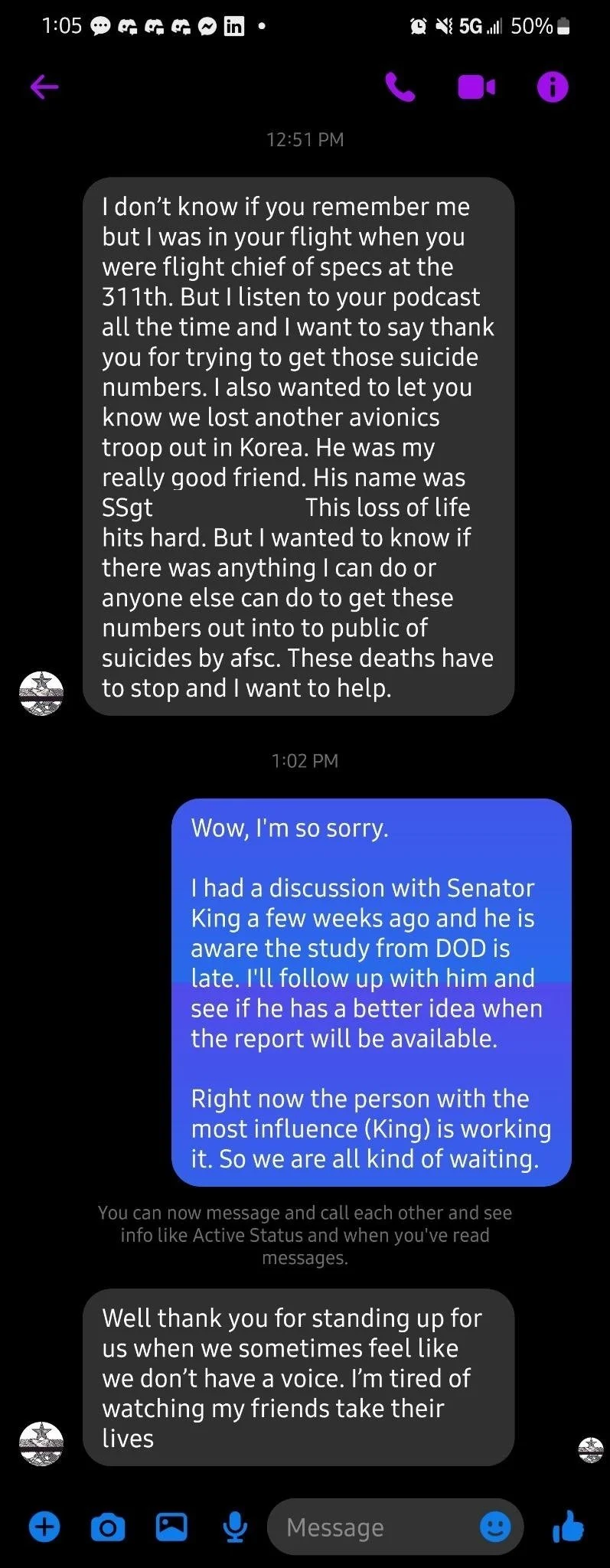

On March 8, 2024, I received a message from an Air Force aircraft maintainer informing me that his friend, stationed in South Korea, had taken his own life.

To emphasize the urgency of the issue, I forwarded a redacted screenshot of the message to Senator King’s staff, attaching it to an email addressed to Jeff Bennett.

In the email, I wrote that the suicide underscored the human cost of continued inaction. I explained that the Report required by Section 599 represented more than data collection—it offered a sense of visibility and hope to servicemembers who felt unseen. I urged Senator King’s office to treat the delay as an immediate concern and to push for the release of the Report with appropriate urgency.

Bennett replied the same day: “Hi Chris—Thanks for the note. I will be getting a substantive update on this matter from DoD very shortly (by 8 April). We are looking at several MH [Mental Health] issues and initiatives as well. Thanks for connecting, too

By this point, the Report was three months overdue, and Bennett had already claimed in January that it was in “final review.” Yet instead of pressing the DoD for immediate accountability, he accepted another thirty-day window before expecting an update. The tone of the exchange reflected routine handling rather than urgency, even in the wake of another suicide within the ranks.

On March 11, 2024, I released a podcast episode documenting my outreach to every office on the House and Senate Armed Services Committees, except Senator King’s. In each call, I explained that the DoD had missed the statutory deadline for the Section 599 Suicide Report and that an active-duty airman had recently taken his own life in South Korea. I asked each office what action they were taking to compel the Report’s release.

That same day, I published an open letter on my 20 Years Done blog addressed to all Congressional Armed Services Committee members. The letter outlined the legal requirement, detailed the significance of the data, and emphasized the urgency of the situation. It called for immediate oversight action to enforce compliance from the DoD and to signal to servicemembers that their lives were not being treated as expendable statistics.

On July 25, 2024, seven months and twenty-five days after the Report was due it was publicly released.

The Unraveling

On July 25, 2024 the DOD released the Suicide Report required by Section 599 of the FY23 NDAA.

The Report did not comply with the law.

It did not include year-by-year data, despite the statute’s clear mandate. Page two of the Report stated: “Suicide rates are not disaggregated by year because doing so would not provide sufficient data to calculate a suicide rate for the military occupations.” It also failed to use service-specific occupational codes such as MOS, AFSC, or NEC. Instead, it relied on generic DoD “Primary Occupation codes” from a central database, explaining: “To identify military job codes or groups for each DoD Service member who died by suicide consistently across time and between the Service Branches, this analysis and Report are based on DoD Primary Occupation codes from the DoD-level master Occupational Database.”

Despite these clear violations of the law, Senator King’s office issued a press release celebrating the Report. The release read: “This newly released Department of Defense report, requested at the suggestion of a smart and savvy Maine veteran, will ensure that the DoD has the most accurate information to help address the risk of suicide amongst the highest risk groups of the Armed Forces while addressing underlying cultural challenges.” Senator King further claimed that the Report was “broken down by military occupational specialty, service, and grade.”

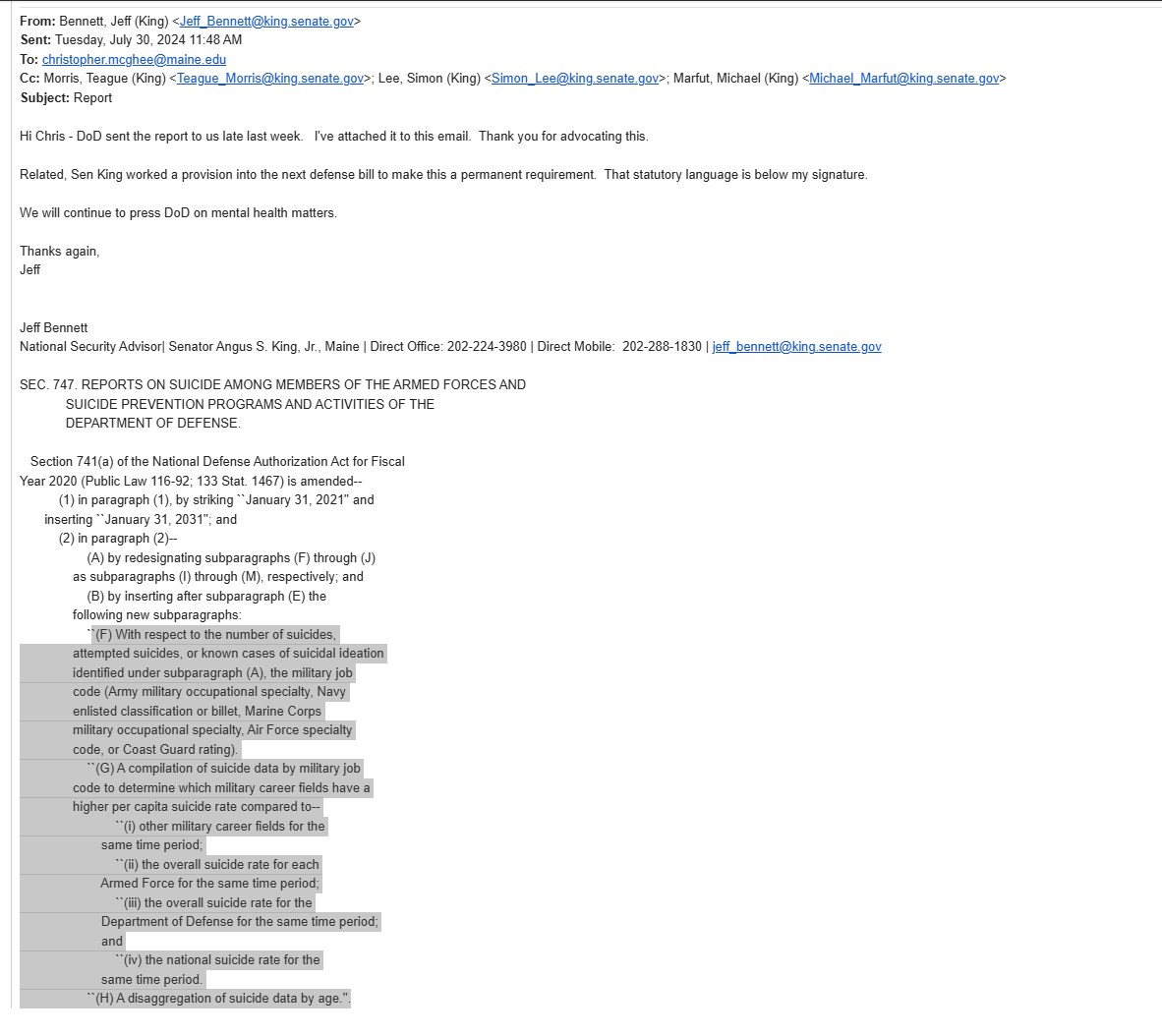

On July 30, 2024, I emailed Jeff Bennett asking for his thoughts on the newly released DoD Suicide Report. I had already reviewed it and knew it violated the law. I wanted to see whether he would acknowledge the shortcomings.

Bennett replied: “Hi Chris – Thanks. This is some good data, and helps focus efforts. We have more work to do and more oversight. In terms of next steps, it includes how the Dept is going to use this information for starters. Also, we will be digging into USCG [United States Coast Guard] data, too. … That’s first blush. More work to do.”

His email did not mention the lack of year-by-year disaggregation, or the use of DoD-level occupation codes rather than service-specific codes.

Bennett also attached draft FY25 NDAA language, labeled Section 747. It strengthened requirements by adding suicides, suicide attempts, and suicidal ideation, disaggregated by service-specific occupational code, age, and comparative rates.

On August 12, 2024, I spoke with Jeff Bennett regarding the Suicide Report. I wanted to understand how much he and the Senator were aware of the Report’s legal deficiencies and whether any steps had been taken to address them.

During the call, Bennett said he received the Report on a Friday evening while traveling and forwarded it to me within a day of returning to his email. When I asked whether he had known in advance that the DoD planned to aggregate the data instead of disaggregating it as required by law, he said he had not and offered no indication that the issue had been raised beforehand.

When I pressed on whether there had been any pushback to the DoD for failing to follow the law, Bennett acknowledged that the report “needed work” but described it as “a step in the right direction.” He said the next steps would be to “follow up” and determine what the DoD was “doing about it.”

I pointed out that the law had been written explicitly to require disaggregated data. Bennett responded that there were “challenges disaggregating the data,” but when asked to specify those challenges, he admitted he had not posed that question to the DoD. Later, he said he had “read [the report] again within the last three weeks” but had “not refreshed” and was focused instead on how DoD planned to use the data.

When I asked if Senator King was aware that the report did not comply with the law, Bennett said he had not explained the legal discrepancies to the Senator. He added that Senator King had read the report “page by page” but was “focused on what the report says and what we do about it” rather than its failure to meet statutory requirements.

This exchange raised an unavoidable contradiction.

Bennett claimed both to have read the report (twice!) and to be unaware that it failed to meet the explicit terms of the law he personally helped draft. Given his familiarity with military occupational codes and the report’s clear language declining to disaggregate by year or service-specific code, it strains credibility to believe he could have read it without recognizing its noncompliance.

The Rot in the Legislative Fabric

On August 15, 2024, after growing doubts about Bennett’s candor in prior discussions, I began researching his professional background. I discovered that Bennett had been relieved of command in 2017 following the fatal USS John S. McCain and USS Fitzgerald collisions. Both disasters were linked to crew fatigue and overwork, and Bennett was removed for “loss of confidence” in his leadership.

The continuity between Bennett’s past failures in command and his current role advising on suicide oversight illustrates how the same culture that punishes truth-telling and rewards self-preservation persists at the highest levels of policy.

At the end of August 2024 I confirmed the DoD Suicide Report was signed by the Acting Undersecretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness Ashish Vazirani. I decided to review his prior congressional testimony.

In December 2023, just weeks before the DoD Suicide Report was due, and eight months before it was released, Undersecretary Vazirani appeared before the House Armed Services Committee in a hearing on recruiting shortfalls. He testified: “In addition, more broadly, members of Generation Z have low trust in institutions.” His prepared remarks, titled Recruiting Shortfalls and Growing Mistrust: Perceptions of the U.S. Military, focused on the idea that negative public perceptions, fueled by social media, were harming recruitment and retention.

During the same hearing, Representative Jim Banks opened by stating: “The recruiting crisis has multiple underlying causes, not least of which is the proliferation of bad news stories about military life. There is an overwhelming perception of rats in the barracks, suicide rates are climbing...”

The same official who publicly characterized negative coverage of military conditions as a threat to recruiting later authored the Suicide Report that omitted required suicide data.

On August 14, 2024, I emailed Teague Morris to state clearly that I no longer wished to work with Jeff Bennett. By this stage, I had concluded that Bennett was either incompetent or acting in bad faith. He had misrepresented the status of the DoD Suicide Report, admitted not understanding the legal requirements, and failed to meet repeated deadlines. I wrote that Senator King might not fully grasp the depth of the issue because Bennett was shielding him from the truth.

Instead of addressing the concern, Teague forwarded my email to Bennett, who then attempted to coordinate the follow-up meeting himself. This confirmed my fears about the absence of accountability within King’s office. The very person I identified as the problem was again positioned to manage the response.

Bennett later proposed a meeting with Sanjay Kane, the Legislative Director. I accepted the meeting.

On September 15, 2024, I met with Sanjay Kane, Senator King’s Legislative Director, to address the core issue: the DoD Suicide Report did not comply with the law.

Early in the meeting, I asked Kane directly whether the report met the legislative requirements. He replied, “According to DoD, their answer is yes. The real question is, do they have the data? They are telling us they don’t have the data that would stretch back to 2001… is that your understanding as well?” I corrected him, explaining that the DoD does possess the data and that the report itself explicitly stated its refusal to disaggregate by year.

Kane later asked about exclusions between service branches, prompting me to reference the report’s own explanations. When I asked if he had read the report, he admitted he had not.

Toward the end of the discussion, Kane asked what would be helpful moving forward. I told him plainly that I was applying media pressure to compel Senator King to make a public statement. I explained that the situation now pointed to only two possibilities: either gross incompetence by Bennett and, by extension, Senator King, or a deliberate effort to undermine King’s own legislation by allowing the DoD to conceal the data.

On September 19, 2024, Senator Angus King sent a formal letter to SECDEF Lloyd Austin acknowledging that the DoD Suicide Report did not comply with the law. King wrote: “I am concerned that the Department did not fully comply with the requirements of Section 599 of Public Law 117-263… Specifically, the Department did not provide disaggregated data dating back to 2001, nor did the Department disaggregate suicide rate data year-by-year.”

King requested two remedies: (1) disaggregated suicide rates for each occupational code for each year back to 2001, with caveats for small sample sizes, and (2) the raw data of suicides by occupational code and year, even where counts fell below 20. He set a deadline of November 1, 2024, for the Department to provide the missing data and a timeline for redoing the report.

This development created an unavoidable inconsistency. On July 30, King’s office issued a press release describing the Suicide Report as “good data.” Seven weeks later, King formally stated that the report did not comply with the law. Both statements cannot be true. Either King’s office released public praise for a report they had not read or understood, or they knew it was legally deficient and endorsed it anyway. There is no interpretation that preserves both competence and honesty.

In hindsight, I was unprepared for the meeting with Kane. I should have specified both forms of required disaggregation — by year and by service-specific occupational code. I had explained these requirements so many times to various staffers that I wrongly assumed the Legislative Director already understood them.

On November 5th, 2024 SECDEF Austin was now part of the outgoing administration so the letter demanding anything of him was essentially worthless.

DoD Takes the Loom

In December 2024, Congress enacted Section 736 of the FY25 NDAA, which extended suicide reporting requirements through 2031 and amended the data elements required under Section 741(a) of the FY20 NDAA. The provision closely resembled the draft language Jeff Bennett had circulated in August 2024, but two material changes significantly altered its effect.

First, the final version removed language requiring the inclusion of suicide attempts and documented suicidal ideation that appeared in the August draft. Second, it added a new clause allowing the DoD to withhold occupational data “excluding such specialties that the Secretary determines would not provide statistically valid data.” This single sentence granted DoD the discretion to decide which occupational codes would be reported — authority that directly contradicts the intent of Section 599 of the FY23 NDAA, which required full disaggregation without exception.

The result was a quiet transfer of legislative control. Instead of compelling compliance with the existing law, Congress adopted language that codified DoD’s preferred approach, giving the DoD the power to determine the boundaries of its own oversight. The overseen had become the overseer.

Where One Thread Ends

From January 2022 to November 2023, Senator Angus King and his staff publicly championed legislation requiring the DoD to release suicide data broken down by occupation and year. While initially strong advocates, the record shows a sharp shift beginning in late 2023, coinciding with testimony by Undersecretary Ashish Vazirani warning Congress that negative perceptions of the military on social media were harming recruitment and retention.

When the mandated report was finally released on July 30, 2024, it failed to comply with the law. It did not disaggregate suicides by year or by service-specific occupational codes, both explicit requirements of Section 599. Despite these omissions, King’s office issued a press release praising the report as “good data.”

Correspondence and meetings with King’s staff indicate that no one in his office had fully reviewed the report before endorsing it. Jeff Bennett, King’s National Security Advisor, admitted in August he had only given it a superficial look. On September 15, Legislative Director Sanjay Kane confirmed he had not read it at all. Only after sustained political pressure did King acknowledge, in a September 19 letter to SECDEF Austin, that the report was legally insufficient, yet his criticism was limited to the absence of year-by-year data, omitting the equally critical lack of service-specific occupational breakdowns.

The report’s seven-month delay suggests that DoD may have reworked its presentation after Vazirani’s December 2023 testimony. Once senior officials and congressional staff recognized that full disclosure could damage recruiting narratives, appearances suggest they sanctioned a version that obscured risk instead of revealing it.

With the new FY25 NDAA language, DoD has solidified its hold over this data going forward, and Congress has abdicated its oversight authority.

In August 2023, when Senator King was still gung-ho for the Suicide Report as it was written and assuring me through correspondence that it would be on time, he gave an interview to News Center Maine captured below.

He said he didn’t want to have any regrets, but regret requires accountability. If no one knows, or cares, about the debacle of this Suicide Report then Senator King doesn’t have to face any accountability, and there won’t be any feelings of regret.

But the data exist. Every omission, every redaction, every reshaped number sits on a server somewhere, waiting. When it comes out, it will not just expose the rate of loss but the architecture of concealment. The deliberate decision to protect an institution’s image over its people. The first harm is what the data describe. The second is what leaders, both in the DoD and Congress, did to keep it unseen.

What Happens Next?

I have the disaggregated suicide data by AFSC from 2010 to 2023.